The constitution’s extensive amendments and inclusion of local government rules make Alabama’s constitution the country’s longest

This essay is part of a 50-state series about the nation’s constitutions. We’ve asked an expert from each state to dive into their constitution, narrate its history, identify its quirks, and summarize its most essential components for our readers.

Alabama has been governed under seven constitutions. The 1901 constitution, which remained in effect longer than its five predecessors combined, was described by one law review article as “specifically designed to maintain the antebellum system of white supremacy.” After decades of critical scholarship and calls to improve it, organize it, and strip it of racist language, Alabama adopted a new constitution in 2022.

But that constitution was derived by and large from the 1901 document, meaning the vestiges of Alabama’s discriminatory foundations remain. Another result? It’s the nation’s longest and most unwieldy state constitution.

Advancement Toward Equality, Then Retractions

Of Alabama’s seven constitutions, only the latter three were ratified by the electorate. The first three — in 1819, 1861, and 1865 — became operable after adoption at the constitutional conventions that created them, reflecting Alabama’s emergence as a new state in 1819 and the evolving circumstances of the Civil War from 1861–1865.

The 1868 constitution, also known as the Reconstruction Constitution, is perhaps Alabama’s most progressive, “guaranteeing the rights of all citizens, protecting the property rights of married women, protecting black suffrage, broadening the voting rights of poor whites, and creating a bureau to promote industrial development,” Joshua Shiver wrote in the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

Importantly, the 1868 constitution was the first to include an equal protection provision, which was retained in the subsequent 1875 constitution: “That all persons resident in this State, born in the United States, or naturalized, or who shall have legally declared their intention to become citizens of the United States, are hereby declared citizens of the State of Alabama, possessing equal civil and political rights and public privileges.”

The 1868 constitutional convention, which met in Montgomery, was comprised of 100 elected delegates, including 18 Black men. According to a history of the Alabama judicial system, while the 1868 constitution included several progressive reforms, the convention splintered along racial lines on questions of Black equality, voting down amendments that segregated public facilities but failing to make an affirmative statement on social equality for Black Americans. At the completion of the 1868 constitution, the history says, a third of “native white Republicans” were against it, and many discontented white Alabamans left early. At the same time, Black Americans were also unhappy with the result.

The 1868 constitution was the first in Alabama to go to voters for ratification. After white Democrats staged a widespread boycott of the ratification election, the constitution did not receive the two-thirds majority required by the Second Reconstruction Act. The U.S. Congress intervened, changing the two-thirds requirement to a simple majority, and making it retroactive so the constitution would be ratified. The Alabama legislature subsequently ratified the 14th Amendment, and the state was formally readmitted to the Union in July 1868.

When Democrats, who were then generally anti-reconstructionist, took control of both the governor’s mansion and the state legislature less than a decade later in 1874, Reconstruction was effectively over in Alabama. A new constitutional convention was held in 1875. Its 99 delegates included only 4 Black men. Many delegates were also Confederate veterans.

The 1875 constitution was ratified by the voters that November and is regarded as a triumph of agrarian interests over the forces of commerce. It abolished the office of lieutenant governor and the State Board of Education. Ultimately, the 1875 constitution “rolled back many of the advances of the [1868 constitution] by reducing the size of government, reducing funds for public education, and weakening the political power of African Americans,” Shiver wrote.

Nevertheless, to many white Alabamians, this retrenchment of civil rights for Black Americans did not go far enough. At the turn of the 20th century, conservative Democrats began to demand a new constitutional convention, in large part to disenfranchise Black Alabamians.

As former Alabama Supreme Court Justice J. Gorman Houston Jr. once noted, all prior Alabama constitutions were occasioned by historical events: statehood in 1819, secession in 1861, post-Civil War reorganization in 1865, Reconstruction in 1868, and its end in 1875. But the 1901 constitution was precipitated by a distinctly ulterior motive. “Historians regard the Constitution of Alabama of 1901 . . . as one not required by historical necessity, but promulgated to effectuate a purpose, to inaugurate a rigidly segregated society and to legalize inequality,” Houston wrote.

Black citizens were systematically excluded from that convention. The convention’s “primary purpose,” University of Alabama professor William Stewart wrote in 2001, was “‘purifying’ the suffrage; in other words, eliminating blacks and, many hoped, radical-minded white farmers who were greatly upsetting things as far as Alabama politics was concerned.”

Records of the constitutional convention show that its president, John B. Knox of Anniston, addressed the delegates, saying “the negro was the prominent factor” in the “issue” to be addressed by the convention. Pushing back against the policies of the Reconstruction era, he added: “It is within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this State.”

The 1901 constitution, the Encyclopedia of Alabama says, perpetuated structural inequality by “concentrat[ing] power in the state legislature, decreas[ing] opportunities for home rule, and establish[ing] voter requirements that even many white men could not meet, reducing the political influence of the state’s many poor whites.” The voter disenfranchisement provisions included poll taxes, a lengthy residency requirement, and disqualification of those deemed “insane” or “idiots[,]” as well as persons convicted of various crimes. The 1901 document also criminalized paying another’s poll taxes or lending money for poll taxes as a form of bribery, punishable by a minimum of one to five years in prison.

In addition, it removed the explicit equal protection provision established in the 1868 constitution. The removal of this provision was premised by those who wanted that redaction on the understanding that the rights were covered by the federal 14th Amendment. The convention records also reiterated the position of some that Black citizens were unqualified to exercise the franchise. Said Knox: “There is a difference, it is claimed with great force, between the uneducated white man and the ignorant negro. There is in the white man an inherited capacity for government, which is wholly wanting in the negro.”

Having stripped Alabama’s local governments of home rule powers to manage their own affairs, the 1901 constitution instead entrusted most of the responsibility for regulating local matters to the state legislature — meaning the state legislature spends much of its session, even today, passing local legislation. “Cities, towns, counties do not govern themselves. We’re governed essentially by their legislative delegations. And to change any law, even to pay a probate judge or to establish a bingo game, you have to amend the 1901 constitution,” Wayne Flynt, a professor emeritus in Auburn University’s history department, said in 2009.

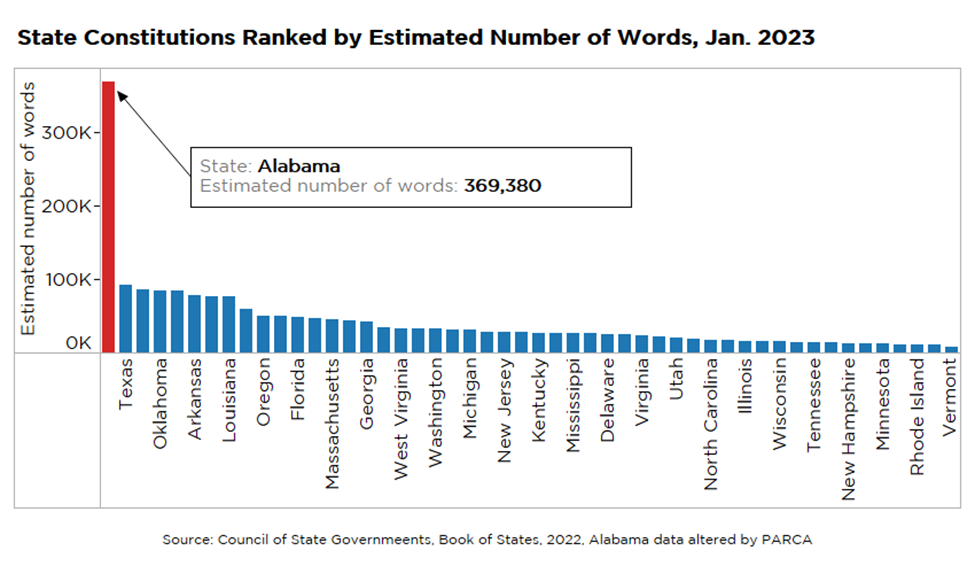

Following its adoption by statewide vote in November 1901, the constitution rapidly grew in length as local measures were added as amendments. By 2009, the Alabama Constitution had been amended more than 700 times and was 40 times longer than the U.S. Constitution.

It was in a 1914 address that Alabama Gov. Emmet O’Neal said, “No real or permanent progress is possible in Alabama until the present fundamental law is thoroughly revised and adapted to meet present conditions.” Nevertheless, the 1901 constitution remained in effect for more than a century.

In 2020, after decades of calls for change, voters approved a constitutional amendment that authorized the legislature to prepare a new version of the state constitution. Alabama voters ratified the revised and reorganized constitution on November 8, 2022. While the 2022 revision of the Alabama Constitution aimed to remove racist language, get rid of repealed provisions, and better organize the document, a press report described the 2022 constitution as “a pretty limited update, aimed mostly at modernizing some text and making it easier to read.” According to the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama, even after passing the new constitution, Alabama remains “governed by the basic operating system established by the 1901 Constitution.”

Declaration of Rights

The Declaration of Rights is Article I of the Alabama Constitution. It “recognizes that individuals possess basic rights that cannot be taken from them by the majority acting through the legislative, executive, or judicial departments of government,” the supreme court justice Houston wrote.

Section 1 paraphrases the Declaration of Independence, pronouncing “that all men are equally free and independent; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Section 2 asserts that “all political power is inherent in the people.”

Several provisions of Alabama’s Declaration of Rights parallel principles established by the U.S. Constitution, including the right to free exercise of religion and the prohibition against establishing a state religion by law, the right to free speech and press liberty, the prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures, the rights to a speedy criminal trial, the right to trial by jury, and the right to bear arms.

The Declaration of Rights provides “that excessive fines shall not be imposed, nor cruel or unusual punishment inflicted,” and “that no person shall be imprisoned for debt.” Additionally, “the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended by the authorities of this state.”

There are provisions that differ from the federal Constitution as well. Alabama’s 2022 constitution incorporated the state religious freedom amendment into the Declaration of Rights, which describes its purpose as “to guarantee that the freedom of religion is not burdened by state and local law; and to provide a claim or defense to persons whose religious freedom is burdened by government.” The amendment empowers any “person whose religious freedom has been burdened” to seek “appropriate relief against a government.”

The Declaration of Rights also says the Ten Commandments can be displayed on state property and in public schools, though only “in a manner that complies with constitutional requirements,” including “being intermingled with historical or educational items, or both, in a larger display.”

Other Unique Characteristics

Alabama’s constitution is about four times as long as Texas’s — the next longest state constitution — and complex even in its updated form.

Despite the goal of the 2022 update to remove redundancies and struck provisions, the extraordinary length is due to the nearly 1,000 amendments added since 1901. Unlike other state constitutions, Alabama’s “is not a basic template and statement of principles,” the public affairs council said, but rather, “more closely resembles a law code, with almost 500 pages worth of amendments that relate to localities rather than to the state as a whole.”

The 2022 constitution sorts local provisions by county at the end of the document. Examples of local measures include a provision authorizing Shelby County to provide “litter, trash, and rubbish regulation,” a provision approving a special tax in Chambers County “for library purposes,” and a provision authorizing Chilton County’s control of dangerous dogs.

As part of its constitutional revision in 2022, Alabama joined Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont (whose voters approved similar language changes in that election) in amending provisions relating to slavery and involuntary servitude. Like the 13th Amendment, Alabama’s 1901 constitution “prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude, ‘except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.’” This “Punishment Clause” exception, originating in the U.S. Constitution and reproduced in state constitutions throughout the country, has been criticized for allowing states to target Black Americans with stiff legal punishments and for using the criminal justice system to recreate a type of slavery.

The Alabama Constitution now imposes an absolute ban, declaring that “no form of slavery shall exist in this state; and there shall not be any involuntary servitude.” This strengthening of constitutional prohibitions against slavery and involuntary servitude may create opportunities to challenge forced work programs in state prison labor systems.

Governance

The Alabama Constitution requires the state government be divided into three “distinct” branches — legislative, executive, and judicial.

The legislature consists of a senate and a house of representatives, made up of no more than 35 senators and 105 house members, with those numbers being its current composition. If additional counties are created, however, each new county is entitled to one representative. Each senator represents a district of approximately 137,000 Alabamians.

The constitution says the “executive department” consists of a governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, state auditor, secretary of state, state treasurer, superintendent of education, commissioner of agriculture and industries, and a sheriff for each county. They are elected positions.

For the judicial branch, the constitution provides there be a supreme court; a court of criminal appeals; a court of civil appeals; a trial court of general jurisdiction, known as the circuit court; a trial court of limited jurisdiction, known as the district court; a probate court; and municipal courts.

“All judges shall be elected by vote of the electors within the territorial jurisdiction of their respective courts,” the constitution says.

Amendments

As mentioned, the Alabama Constitution has been amended hundreds of times to resolve developing state and local issues.

The amendment process is itself somewhat cumbersome, including requirements that the proposed amendment be read on three days in the legislative house proposing it, then approval by three-fifths of that house, then to a public election on a specified day. A simple majority is required for it to pass.

Judicial Interpretation and Limiting Equal Protection

Ex parte Melof, decided in 1999, is one of the most important cases interpreting the Alabama Constitution. In upholding the state’s retirement benefit taxation classifications against an equal protection challenge, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that the Alabama Constitution does not provide an equal protection guarantee, as the express equal protection provision was removed during drafting of the 1901 constitution.

The state supreme court had recognized the existence of a state guarantee of equal protection in a line of cases going back decades. However, the Melof court reviewed the proceedings of the 1901 convention and the development of its own case law and concluded that the finding of a state equal protection guarantee was mistakenly premised on “an erroneous unofficial annotation” that was included in a printing of the Alabama Code in 1940 and in subsequent editions. This annotation was then relied upon and quoted by the Alabama Supreme Court in its decisions.

The dissenters in Melof and other critics of the decision have pointed to other provisions of the Alabama Constitution which may be interpreted to convey an equal protection guarantee, such as a provision in the Declaration of Rights “that all men are equally free and independent.” But Houston, who authored Melof, has explained that the Alabama Supreme Court cannot simply overlook the racist designs of the framers of the 1901 constitution, and instead advocated constitutional reform: “We cannot change history. Alabama in 1901 was Alabama in 1901. However, Alabama will be remiss if it enters too far into the new century with a constitution having as its main purpose to establish a segregated society and to legalize inequality.”

The express equal protection provision omitted by the 1901 convention remains absent from Alabama’s constitution.

Ex parte James, in 2002, is another important case of constitutional interpretation. In James, the Alabama Supreme Court brought a swift end to what was known for years in Alabama as the “Equity Funding Case,” which alleged the state was infringing on Alabama schoolchildren’s rights by failing to provide an adequate and equitable public education as required by the 1901 Alabama Constitution.

In 1992, a lengthy trial was held, revealing the pitiable state of public education in Alabama due to the lack of adequate funding. The trial court ruled that Amendment 111 of the state constitution, enacted in 1956 “in an attempt to evade compliance with the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion in Brown v. Board of Education,” violates federal equal protection guarantees.

But the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that the judiciary was constitutionally prohibited from providing a remedy for the problem of inadequate school funding. “The pronouncement of a specific remedy ‘from the bench’ would necessarily represent an exercise of the power of that branch of government charged by the people of the State of Alabama with the sole duty to administer state funds to public schools: the Alabama Legislature.” Accordingly, the Alabama Supreme Court dismissed the litigation. Portions of Amendment 111 were eventually removed from the state constitution by public vote.

• • •

By removing explicitly racist language and reorganizing the lengthy text, the 2022 revision to the state constitution represents an important and necessary step forward for Alabama. But as the current constitution is derived largely from the 1901 constitution, advocates believe additional reform will be necessary to fully remove its discriminatory foundations, empower local governments to meet the needs of their constituents, and improve the provision of public education.

Keisha Stokes-Hough is a deputy director of legal management at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

A correction was made on July 16, 2025: An earlier version of this article stated that Amendment 111 was removed from the state constitution in its entirety. However, only portions were removed.

Keisha Stokes-Hough is a deputy director of legal management at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Suggested Citation: Keisha Stokes-Hough, The Alabama Constitution: Despite a Century of Updates, Traces of its Racist Past Linger, Sᴛᴀᴛᴇ Cᴏᴜʀᴛ Rᴇᴘᴏʀᴛ (Jul. 8, 2025), https://statecourtreport.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/alabama-constitution-despite-century-updates-traces-its-racist-past